|

|

Image Credit: Microsoft Stock Images |

Artificial intelligence (AI) influences many aspects of modern life and has multiple applications. AI is the ability of machines or software to perform tasks that are commonly associated with human intelligence, such as recognizing patterns, making decisions, or learning from data. AI is designed to mimic human capabilities, including pattern recognition, data analysis, and decision-making, and to perform tasks rapidly and efficiently.

Algorithms are a set of problem-solving steps computer programs use to accomplish tasks. AI operationalizes the algorithmic steps in smart machines that perform tasks usually associated with human intelligence such as “learning, adapting, synthesizing, self-correction, and use of data for complex processing” (Popenici & Kerr, 2017, para. 3). Machine learning is an application of AI in which large data sets are analyzed, without direct instruction, to detect patterns that might elude human beings. Generative AI is an artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content, including text, imagery, audio, and synthetic data.

AI originated in the 20th century, but only recently have computers had the computational power to make it practical and useful (Anyoha, 2017). Most people are using AI without recognition because AI powers internet search platforms, predictive text, grammar- and spell-check, GPS, social media curation, smart devices, streaming services, and patient portals. Many people conflate generative AI with large-language models such as those used within ChatGPT, but this is only one type of AI.

Typologies of AI

It is essential to recognize that AI is multifaceted and has multiple applications. Therefore, it can be categorized in multiple ways: based on capability, functionality, application, or degree of supervision vs. autonomy.

Capability

One capability-based categorization is weak and strong or general AI. Narrow or weak AI can perform single-specific tasks such as making Netflix recommendations, facial recognition, self-driving cars, searching the internet, or translating languages. General or Strong AI can perform tasks in a human-like manner (AVContent Team, 2023). Some descriptions differentiate general AI from strong AI, with the former referring to a computer that is as smart as a human in a general sense and the latter referring to computers that have achieved human consciousness. The latter category is still somewhat theoretical because AI has not yet achieved consciousness or self-awareness. This counteracts the idea that sentient robots will take over the world and enslave humans, as many science fiction novels and films would have people believe. Think of the Terminator or 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Another capability-based typology characterizes four levels of AI: (a) reactive, (b) limited memory, (c) theory of mind, and (d) self-awareness. Consistent with the weak vs strong typology, this conceptualization indicates that AI has not yet achieved theory of mind, meaning the capacity “to understand and remember other entities' emotions and needs and adjust their behavior based on these. This capability is like humans in social interaction” (Arya, 2023, para. 13). Humans develop this capacity as they mature. They also develop self-awareness and emotional intelligence, while AI does not.

|

|

Four Levels of AI |

Functionality

One functionality categorization scheme asserts three categories of AI: (a) large language models (LLM), (b) learning analytics in which personalized learning is tailored for individuals, and (c) big data, meaning using large data sets to conduct comparative analysis between groups of people. These can be expressed in input and output, instructor and student, or data and functions.

Another functionality schematic suggests the following categories:

· Analytic AI scans large datasets to identify, interpret, and communicate meaningful patterns of data.

· Functional AI scans huge amounts of data to take actions.

· Interactive AI automates communication without compromising on interactivity.

· Text AI uses semantic search and natural language processing to build semantic maps and recognize synonyms to understand the context of user’s question.

· Visual AI identifies, recognizes, classifies, and sorts objects or converts images and videos into insights. (Sarker et al., 2022).

Application

Yet

another way of categorizing AI is by applications in which it is used. For

example, expert systems use information collected from recognized domain

experts to facilitate fast decision-making. Natural language processing (NLP)

enables AI to use language in a human-like manner in chatbots, language

translation, and sentiment analysis, which is used to determine whether the

emotional tone of a message is positive, negative, or neutral. Sentiment

analysis has become an important business function used to improve customer

service, market research, and to monitor brand performance. It can distinguish

the positive from the negative of a seemingly contradictory sentence such as:

“While I liked this product, I was disappointed with the color.”

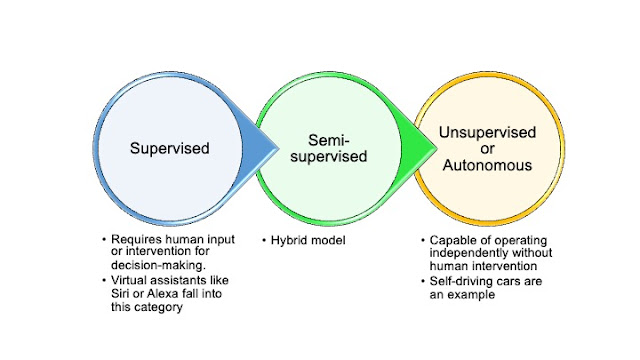

Supervision vs. Autonomy

This typology is often used to describe the process of machine learning, in which:

· Supervised learning—all data are labeled.

· Semi-supervised—some input data are labeled, while some are not.

· Unsupervised—all input data are unlabeled (Alloghani et al., 2020).

These terms can also be used to describe AI. Examples of supervised processing include virtual assistants such as Siri and Alexa, while an example of unsupervised or autonomous processing is self-driving cars.

You may notice overlaps between the different typologies, as the following concept map clarifies.

No matter how you conceptualize it, the field of AI is complex, growing, and rapidly being integrated into multiple fields of professional practice. These typologies highlight the diverse nature of AI, and the various systems designed for specific purposes and possessing different levels of capabilities. The field of AI continues to advance and new typologies may be developed as its capacities evolve.

References

Alloghani, M., Al-Jumeily, D., Mustafina, J., Hussain, A., Aljaaf, A.J. (2020). A systematic review on supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms for data science. In M. Berry, A. Mohamed, & B. Yap (Eds.), Supervised and unsupervised learning for data science. Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Learning. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22475-2_1

Anyoha, R. (2017, August 28). The history of artificial intelligence. Harvard University. Retrieved https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/history-artificial-intelligence/

Arya, N. (2023, November 16). Theory of mind AI in artificial intelligence. Ejable. Retrieved from https://www.ejable.com/tech-corner/ai-machine-learning-and-deep-learning/theory-of-mind-ai-in-artificial-intelligence/#:~:text=Theory%20of%20Mind%3A%20This%20is,like%20humans%20in%20social%20interaction.

AVContent Team (2023, September 14). Weak AI vs strong AI: Exploring key differences and future potential of AI. Analytics Vidhya. Retrieved https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2023/04/weak-ai-vs-strong-ai/

Popenici, S. A. D., & Kerr, S. (2017). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning,12, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8

Sarker, I.H. (2022). AI-based modeling: Techniques, applications and research issues towards automation, intelligent and smart systems. SN Computer Science,. 3, 158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01043-x